Chances are you’ve bumped into the phrase Christian nationalism, usually referring to a movement, person, or idea that believes America was founded not only on Christian ideals and principles, but the country is to be Christian—and that Christians are called to work toward that end.

Think of it as a wide tent. At one end: “I wish my country were more Christian, and I pray and work toward that.” At the other end: “Since my country was founded by God to be Christian, we should use government laws and policies to enforce Christian values and rules.” Between these poles lies a full range of views. It is the latter, more coercive version that has caught public attention, and it is often what people mean when they use the term today. Its loudest voice is in the United States.

My caution to friends is simply this: let’s be careful we don’t collapse all these views into one. Many Christians sincerely long for their country to reflect Christ and his rule. But when it takes on the words of being coercive, and to use the law in a compelling way—using the state to insist the nation be Christian—one might call that, not Christian nationalism, but Christian supremacy.

At its core, this view holds that the United States has a special, divinely intended identity, from which it follows that its institutions, laws, and cultural norms should explicitly reflect Christianity—usually a particular, conservative expression of it. This goes beyond influence; it seeks a nation in which Christians are able to enact laws and pass policies that are Christian (or Judeo-Christian).

In this case, being “Christian” and being “American” become mutually reinforcing, intertwining loyalty to God with loyalty to country. This is underwritten by a reading of history that claims America was founded as a Christian nation, has since strayed from that calling, and can only recover by restoring Christian symbols, language, and authority in public life.

Politically, this vision almost always aligns with the Republican Party, framed as the party most faithful to the gospel—especially on issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, and transgender legislation.

As a non-American, I do not judge how Americans read their history or whether they see their nation as divinely mandated. I do view Canada’s founding as deeply shaped by a Christian vision of life—sometimes nominal, sometimes active—in which God is Creator and Jesus is our access to God and providence. With that history, and with a desire for the gospel to be salt and light in our land, I, too, seek greater Christian influence in our nation, its people, laws, and traditions. So, am I a Christian nationalist?

A bit of history

While this movement is surprising, it does have a long history. The early church in Asia Minor (part of Turkey today) generally lived under harsh treatment by its political lords, especially under Roman rule. But in 312 AD, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great, entering into a battle, reportedly heard a voice, “By this sign shalt thou conquer,” referring to Christ’s cross. After his victory and conversion, Constantine gave Christians under Roman rule freedoms they had never had.

Over time Christians began to take on prominent roles in society, and eventually, the church helped set rules for the empire, obliterating what we often call today the separation between church and state. (This practice is known as Constantinianism, or sometimes as Christendom; in its most extreme forms, the church and state act as one.) For many centuries thereafter, the Christendom model functioned in both the eastern (Orthodox) and western (Roman Catholic) areas of Christianity, until it was challenged during the Reformation. In some countries, Protestants simply replaced Roman Catholics as the dominant faith and were linked to the political elite in the same way as their predecessors.

Today, neither Christian nor other sorts of religious nationalisms are restricted to America. While in Greece, I listened to a father’s story who had to go to court to get the government to register the birth of their child, because he wasn’t baptized in the Greek Orthodox Church. In India, the Hindutva movement is pressing the government to insist that India be covered by Hindu laws, insisting that its country accept that the religious and cultural cloak of Hinduism was essential to the character of the country. Hindutva, with its family resemblance to Christian Nationalism, holds that India is fundamentally Hindu, and that national culture, law, and public life should reflect Hindu civilizational values.

In the middle of change

We are living through a profound transition. Long-held assumptions in North America—that biblical ethics would naturally shape public life—no longer hold. This unsettles us. We search for new ways for Christian witness to endure in a secular age. We should not underestimate how deeply this transition affects us all.

Our responses are shaped by many factors—nation, church tradition, denomination, age, and social location. These differences can harden into suspicion. Social media amplifies this, pushing us to say things we would never say face-to-face.

Which brings us full circle: what does this have to do with Jesus? For some, Christian Nationalism has become a hammer—used by critics to strike hard, and by defenders to strike back. The result is bitterness that fractures families, friendships, and congregations.

So, let’s search for a better way. We might begin with this agreement: Jesus is Lord of all, and our shared aim is to see his life reflected in the world. From that, we might move to agreeing to refuse resorting to name-calling, to stop making judgments on each other, to not reduce each other to labels, nor attach identity because of political affiliations. With that as a base, using this as a common confession, we pray that our lives will engage civic life in different ways—graciously, prayerfully—working for a Christian influence that permeates society, strengthens families, and gives moral weight to our common life.

Social movements rise and fall. What feels decisive now often fades in hindsight. What endures is how we treated one another, and whether our witness reflected the character of Christ. I feel this debate personally. Raised in a Pentecostal pastor’s home, I remember the sharp edges of evangelical criticism—“holy rollers,” they called us. Some criticism was deserved. We were changing. We made mistakes. Our theology needed grounding. But we were also on the edge of a genuine work of God, a movement that has spread globally, something we see clearer now in hindsight.

That memory shapes how I see this moment. God is at work among us again, even amid confusion. Not everything said is from him. That calls us not to denunciation, but to discernment. The easiest move is to discredit. The harder and truer one is humility.

What Jesus said

Jesus addressed this directly. Asked whether Jews should pay Roman taxes, he requested a coin. The coin declared Caesar’s divinity—power backed by money. Jesus said, “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” then turned the logic upside down: “and give to God what is God’s.” Jesus asserted divine authority without money, office, or force. Our instinct, by contrast, is to reach for political levers and replace those in power.

What lies embedded in Jesus’ answer is something startling: humility. His way flows into the cracks of life. Humility is the oil of the kingdom. It holds on to nothing and promises nothing it cannot deliver. It is not weakness or passivity. It is full-bodied, dynamic, and daring. It opens doors rather than battering them down. It defies power-seekers with a witness that, over time, outlasts Caesar.

Whatever our political views, we confess that Jesus will establish a reign that is total and complete. Our hope rests there. The question is not whether Christ will rule, but how he wants his rule to be among us now. Jesus’ answer is clear: a revolution without power, money, or status. His kingdom comes not by election but by crucifixion. Caesar and Jesus both wield power—but of radically different kinds. And it was through the cross, not the sword, that Jesus’ power was finally revealed for the good of creation and the glory of God.

And in our debates, a little humility would look good on us all.

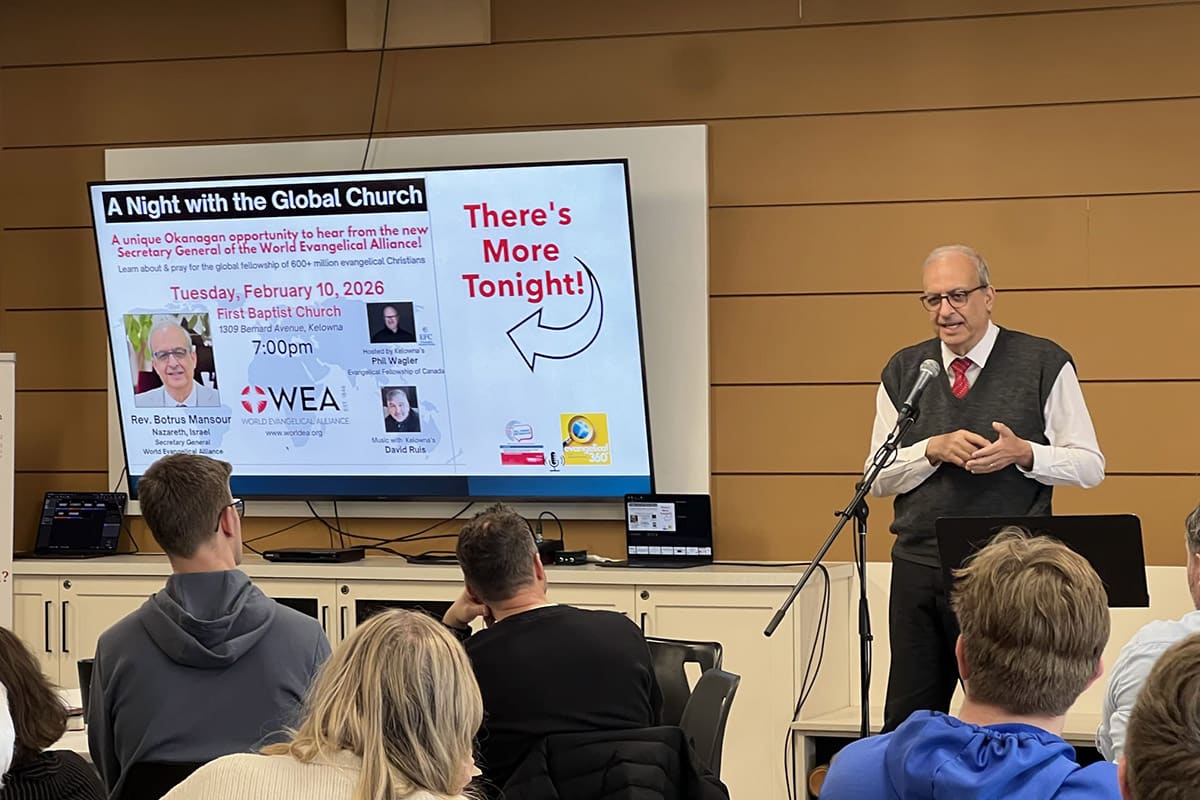

Brian Stiller

Global Ambassador, World Evangelical Alliance

February 2026

Stay Connected