By Nicolai Franz

Translated with permission from the German original in the Christian media magazine PRO (pro-medienmagazin.de).

A German will soon represent 600 million Christians as Secretary General of the World Evangelical Alliance: Thomas Schirrmacher. He has been involved on the big stage of politics and religion for decades. He will be inaugurated into his new office on February 27.

Anyone attempting to describe Thomas Schirrmacher in brief terms can only fail. He is a theologian, sociologist of religion, cultural anthropologist, author, human rights expert, and bishop. He has written more than 100 books, four doctoral theses and a seven-volume series on ethics, and he has served as rector of the Martin Bucer Seminary. That alone would be enough to fill a particularly committed academic life well into retirement.

But that is only one side of the 60-year-old. He was a pastor, has led several human rights organizations, fights against human trafficking, has published the Yearbook on the Persecution of Christians for 20 years, meets with the leaders of the world’s religions and political parties, and has worked as an expert for the Bundestag. Unquestionably, Schirrmacher is a multi-talent, such an extraordinary one that no observer could have been surprised when he was elected Secretary General of the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) in 2020. As of March 2021, he will represent the world’s 600 million evangelicals.

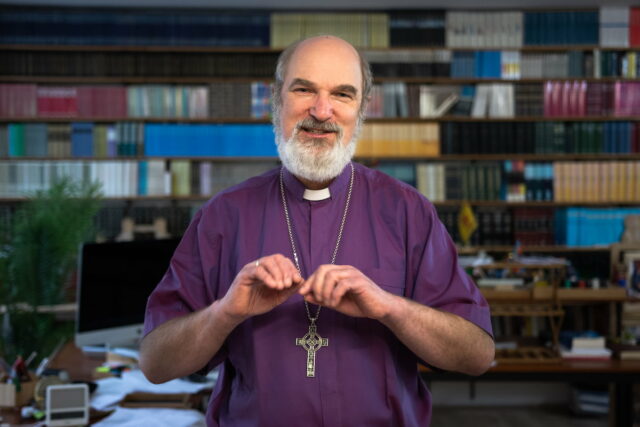

When we met Thomas Schirrmacher in January, for the photo he slipped into his bishop’s shirt, the massive cross of course not missing. As a bishop, he has been responsible for the “Communio Messianica” with a conservative Anglican outlook since 2016. The group consists of Muslims who have converted to Christianity. He shares a huge office, containing thousands of books, with his wife Christine, a respected Islamic scholar. As WEA Secretary General, Schirrmacher will mainly do networking and diplomacy – areas in which he is battle-hardened.

In his previous functions, including as Associate Secretary General, he was already engaged in continuous global work for the WEA – often to put out fires, especially concerning religious freedom. In 2020, he mediated between churches, Muslims and politicians in The Gambia to prevent the introduction of a Sharia-influenced constitution. In 2017, he met the Grand Mufti of Lahore and spoke with him about Pakistan’s controversial blasphemy laws, and in the same year, in a speech in Baku before a large crowd of Muslim clerics, he advocated protecting Christian minorities. “I am a crisis manager because I hate crises,” he said.

Even where there is peace, Schirrmacher knows how to network. At the 2017 Kirchentag in Berlin, he appeared wearing a bowtie at the reception of the Evangelical Working Group of the CDU, where Angela Merkel also spoke. There he adopted another of his thousand roles: usher. “I knew which international church guests would come and who had no seat reservation,” he explained. “The Archbishop of Canterbury was registered, so it would have been awkward if he had to stand.” After the event, Schirrmacher managed to channel the (evangelical) head of the Church of England through to the Chancellor for a longer conversation. The EKD was not interested in that.

Billy Graham sat at the young Schirrmacher’s lunch table

That is typical of Schirrmacher. Unlike officials of the national churches, he does not have a large apparatus of staff, press spokespersons and infrastructure. He does most of his work under his own steam, supported by a handful of co-workers in Bonn. Press releases, newsletters, book publications – Schirrmacher is never at a loss to disseminate what he has achieved through the media. Could there be a touch of vanity in all this? His father Bernd, a communications engineer at the University for Applied Science of Giessen, taught him at a young age not to be too much in awe of authority. “Who knows how they gained their titles?” he used to say. When his mother once suggested to his father an increase in Thomas’s pocket money, Bernd Schirrmacher casually said that this would fit in quite well with the family finances, as Bernd had been raised to a professorship with a higher salary. “My mother was blindsided, she didn’t even know about it,” Thomas recalled.

Bernd Schirrmacher had co-founded a Christian school in Giessen and was on the board of a global mission society. For the son, it was normal to have contact with influential people even as a child. Such celebrities as the evangelist Billy Graham sat at the Schirrmachers’ dinner table, as did other clergymen from all over the world. “If theology doesn’t reach the house fellowship, it’s worth nothing,” Thomas noted.

When he became pastor of a regional church community in Bonn, then the German capital, in his early twenties, he encountered an ex-general and a former state minister in the group of elders, who were “all such big shots.” The previous three pastors had been worn out, the community leadership told him, but Schirrmacher didn’t care who sat across from him.

In his audacious scurrying around, he embodies the worldwide alliance like hardly anyone else. Although the WEA represents the numerically second-largest movement in Christendom (after the Catholic Church), it is not a church federation, but a loose network with a high degree of autonomy of local congregations and hardly any hierarchical structures. Everyone who shares basic evangelical convictions is welcome. Swarm transcendence instead of church eminence.

The largest debating community in the world

“Evangelicals are incredibly dogmatic on the one hand and incredibly undogmatic on the other,” says Schirrmacher. Some denominations ordain women, others do not. But it is generally accepted that this question is not decisive for salvation: “A church that is against women’s ordination accepts in the week of prayer a church that turns up with a woman.” The same applies in dealing with the Bible, he said: “We are dogmatic in giving the Bible constitutional status.” On the other hand, evangelicals would hold every Christian responsible: “The Alliance Confession of 1846 says that the Bible is the supreme guide in all matters of faith and life of the church. Every believer is obliged to read and judge the Holy Scriptures for himself.”

Outsiders have difficulty understanding evangelicals on this point: “On the one hand, we have a clear foundation, but on the other hand, we are the largest theological debating community in the world. If theology does not reach the house fellowship, it is worth nothing.” He himself holds conservative evangelical positions, such as affirming the Chicago Statement on the Inerrancy of Scripture. But that does not keep him from interreligious dialogue or from social concerns. The presence of a wide range of opinions in the Alliance, whether about sexuality or politics, baptism or piety, is not a problem for him. What matters to him is the core: “The DNA of Christianity is the gospel, and that revolves around Jesus and a personal relationship with him. And how do we know that? From the Bible. That is being evangelical.” Schirrmacher has been friends with Pope Francis for a long time, having met him more than 30 times. Theologically, he sees the Pope as an ally, more so than many a liberal Protestant.

And yet ecumenism in particular requires diplomatic instinct. Schirrmacher has written shelves of books, but his most important work is only five pages long: “Christian Witness in a Multi-Religious World,” the first joint statement by the Vatican, the World Council of Churches and the WEA.

Schirrmacher disclosed private details of that undertaking to us at his office in Bonn, where the conversation lasted several hours. For five years, the responsible persons had struggled over the wording. Out of consideration for other religions, biblical passages were not included as supporting documents. According to Schirrmacher, when the paper was put to a vote in Bangkok in 2011 by the three bodies involved, there were questions over why no biblical passages were included and whether a preamble might be needed. Schirrmacher was prepared for both questions, because the commission had already prepared appropriate drafts.

After a break in the meeting, the commission presented a revised draft, peppered with biblical passages and with a preamble that could hardly be more evangelical. The first words were, “Mission belongs deeply to the nature of the church. Therefore, it is indispensable for every Christian to proclaim God’s Word and to witness to his or her faith in the world. However, it is important that this is done in accordance with the principles of the Gospel, in full respect for and love of all people.” The declaration was accepted and even ratified by all member churches of the EKD, which are otherwise not known for outstanding missionary zeal. A strategic masterstroke – and chalk one up for him in his appointment as head of the WEA.

As WEA leader, he will speak even more forcefully on the world stage for the evangelicals. He is resigning from most of his other offices. But even now there are very few who, like him, almost casually say sentences like “Sometimes on a trip I have time only to meet the president of the Parliament.”

And then there is still a life apart from the ministry. Every year he spends four weeks on a North Sea island with his wife. “The family can tell by the tip of my nose when work gets too much,” he laughed. Even a Schirrmacher needs a break at times.

Stay Connected