In a recent lecture on human dignity, the Archbishop of Canterbury made it clear that in his opinion the world at large is not waiting with bated breath to hear what the Church has to say about morality. So why should anyone be expected to take Christians seriously when they launch a global campaign about corruption?

Lectures about morality from Christian communities with a track record in child abuse and bizarre cases where children have been demonised as witches can seem disingenuous. And there is little encouragement in the fact that according to the Status of Global Missions report in 2010, ‘ecclesiastical crime’ – across all faiths – is on the increase. In 1900 an estimated US$300,000 went missing from religious coffers. In 2010 that figure rose to US$32b and is projected at US$60b by 2025.

Fact and fiction have conspired to paint unpleasant caricatures of pastors pilfering from the offering plate, and preachers growing fat on the sacrifices of their beleaguered congregations. More recently, allegations of theft surrounding the Pope’s former butler, Paolo Gabriele has only served to fuel the fallacious ideas which Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code left so vividly in our minds. Many people still harbour images of the Occupy campaign stalking St Paul’s Cathedral for months and raising questions about the church’s profligate relationship with City banks.

Even so, one of the greatest misnomers about faith is to present it as a panacea of human perfection. As someone once suggested, the Church is like Noah’s Ark: smelly on the inside but arguably safer than swimming in the flood tide outside.

On the way to perfection, religion often stumbles in the streets.

And in a world where corruption kills people, undermines enterprise and stifles development, religion cannot wait for its own perfection before it works to clear up the mess.

Even if faith is culpable it is also responsible. With its guilt intact, faith must turn up for clear-up duty.

And that’s always been the case. Arguably the 16th century Reformation in Europe was perhaps the most profound anti-corruption campaign the world has ever seen. In more recent decades Christian leaders have been at the forefront of fighting against injustice and corruption. Pope John Paul was a tireless campaigner for a better world. Desmond Tutu’s name will forever be a synonym for freedom against the evil of Apartheid in South Africa. And in the United Kingdom Archbishop John Sentamu dramatically destroyed his dog collar on national TV as a personal protest against Mugabe’s corrupt regime in Zimbabwe.

Like everybody else Christians have a right to join the assembly of the imperfect in order to say and do something about the US$1trillion, which goes missing illegally from our economies every year – much of this through illicit flows and undisclosed accounting. Whilst the world's wealthy exploit legal loopholes to hide trillions of dollars in tax havens, some of the poorest people are dying from easily treatable diseases or pay bribes to educate and feed their children. So like everyone else religious people have a role to play in shining a light on the extractive industries which rape nations of their minerals and natural resources in exchange for a pittance. And equally to challenge recipient governments who fail to publish the monies they receive from their unscrupulous tenants.

And Christians have a right to be worried about the cultures of corruption existing in European democracies. According to the Transparency International Corruption Risk 2011 report, “Political parties and businesses exhibit the highest risks of corruption across Europe”.

But people of faith also care about its most deadly impact. It is the moral paralysis which creates the indifference to a problem we deem to be too hot to handle and too overwhelming to do anything about.

So Christians have decided that if they’re a part of it, they may as well start from where they are.

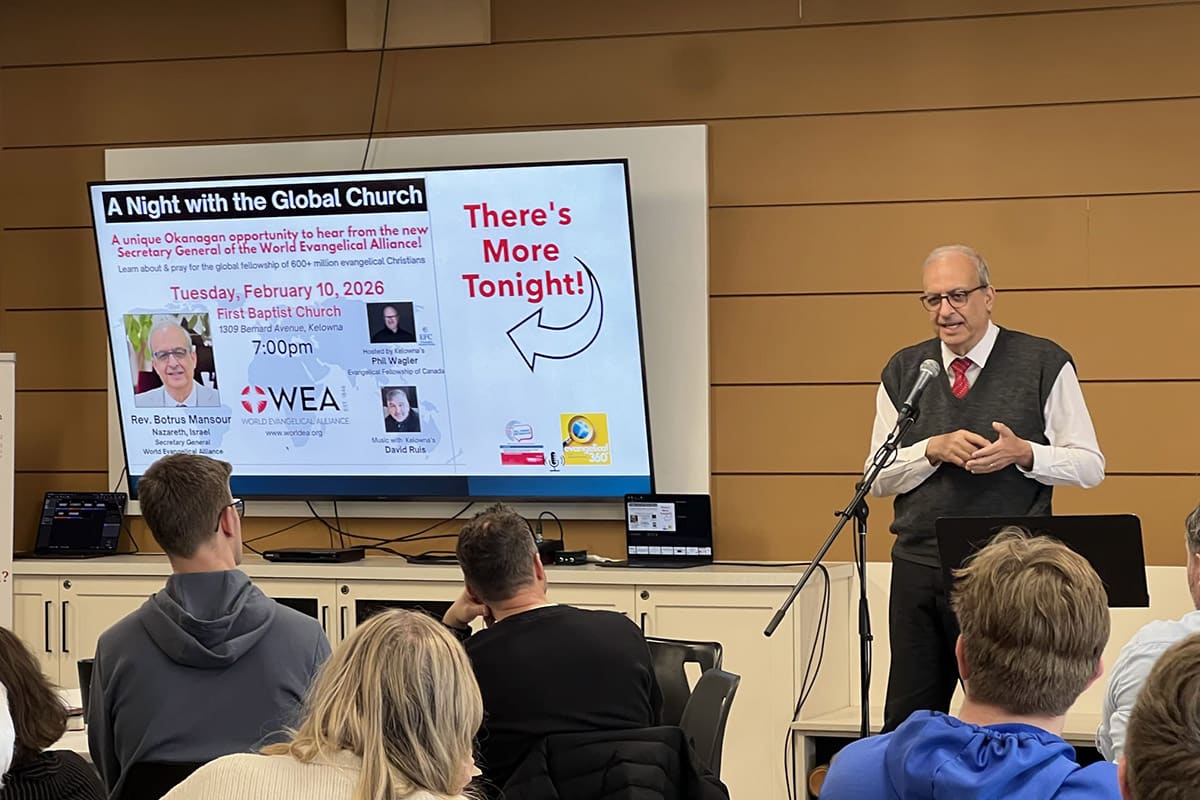

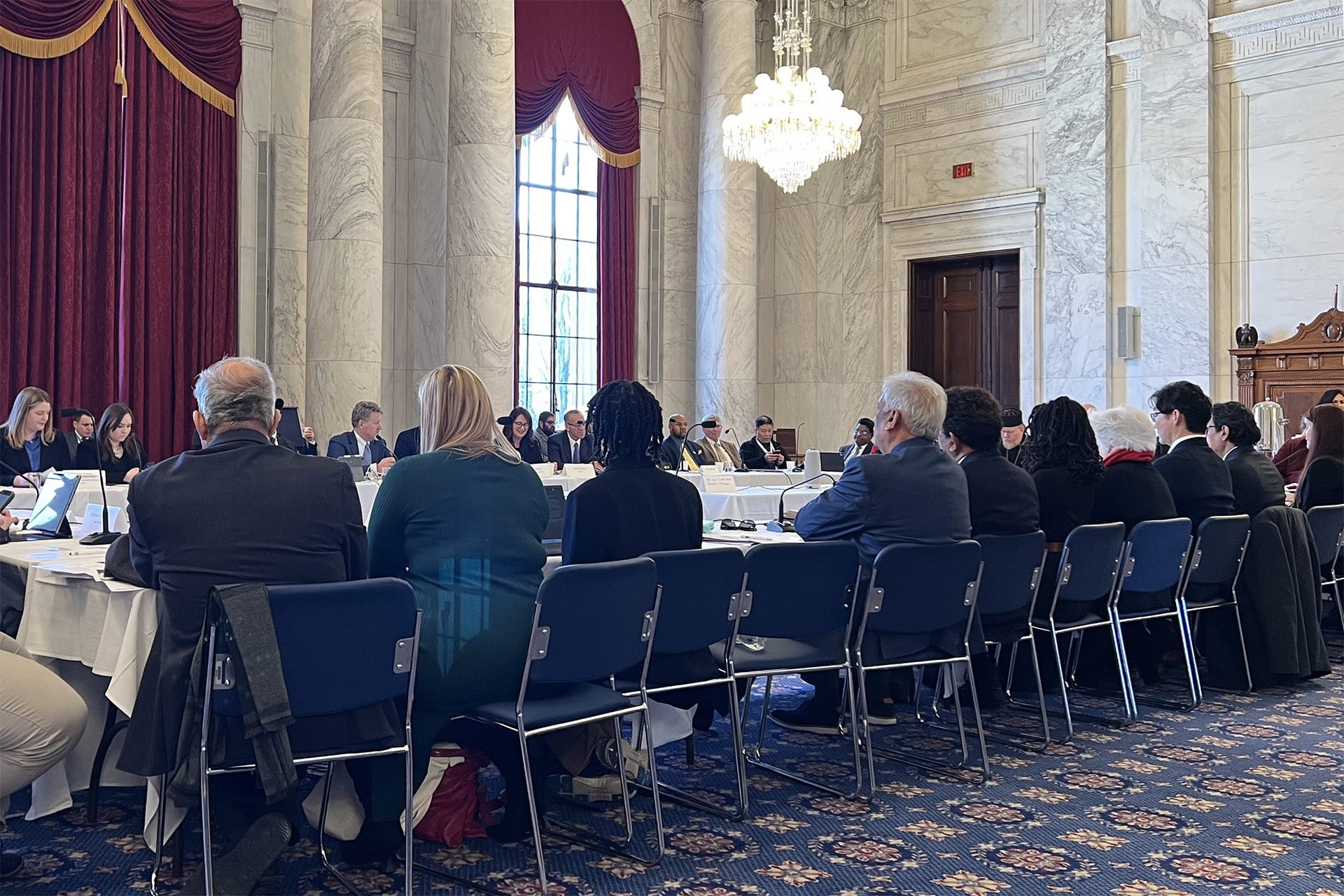

And that’s why EXPOSED2013 has taken up the challenge to shine a light on corruption. In launching its global campaign this week at the Methodist Central Hall in London, the Christian coalition of churches, organisations and NGOs are campaigning for measured impatience at the corruption which is killing people all over the world. Its audacious plan is to mobilize 100 million Christians worldwide to challenge churches, business and governments to take practical and political steps to resist corruption.

The campaign will hold a series of vigils during the week of 14-20 October 2013 and aim to present 10 million signatures at the G20 meeting of world governments in November 2014. And because they believe that, “judgement begins at the house of God,” over 3000 local churches have already signed up to make this a central issue during their Sunday services on 14 October.

Ending extreme poverty is achievable and possible, and tackling corruption is key. Increasingly people of faith are waking up to realize that even if they are a part of the problem they have an even bigger responsibility to be a part of the solution.

Joel Edwards

Rev Joel Edwards is International Director of Micah Challenge and Chair of EXPOSED2013, an international coalition of Christian organisations that aims to challenge the global Church, business and governments to highlight the impact of corruption on the poorest of the poor. The EXPOSED coalition partners include the Bible Society of the United Kingdom, the Bible Society of North America, The Salvation Army, Unashamedly Ethical, the World Evangelical Alliance and Micah Challenge International.

The EXPOSED year of campaigning culminating in a Global Vigil against Corruption planned for 14-20 October 2013 will be launched at Central Hall Westminster at 11am on Thursday 11 October 2012.

Stay Connected